VSEPR Theory and Molecular Geometry

VSEPR Theory and Molecular Geometry

The three-dimensional shape of a molecule drives boiling points, dipoles, and reactivity trends. Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory gives us a fast way to predict molecular geometry by assuming electron groups spread out to minimize repulsion.

Quick Guide

- Electron Groups and Basic Geometries

- Electron Geometry vs Molecular Geometry

- Lone-Pair Effects and Bond Angles

- Polarity and AXE Notation

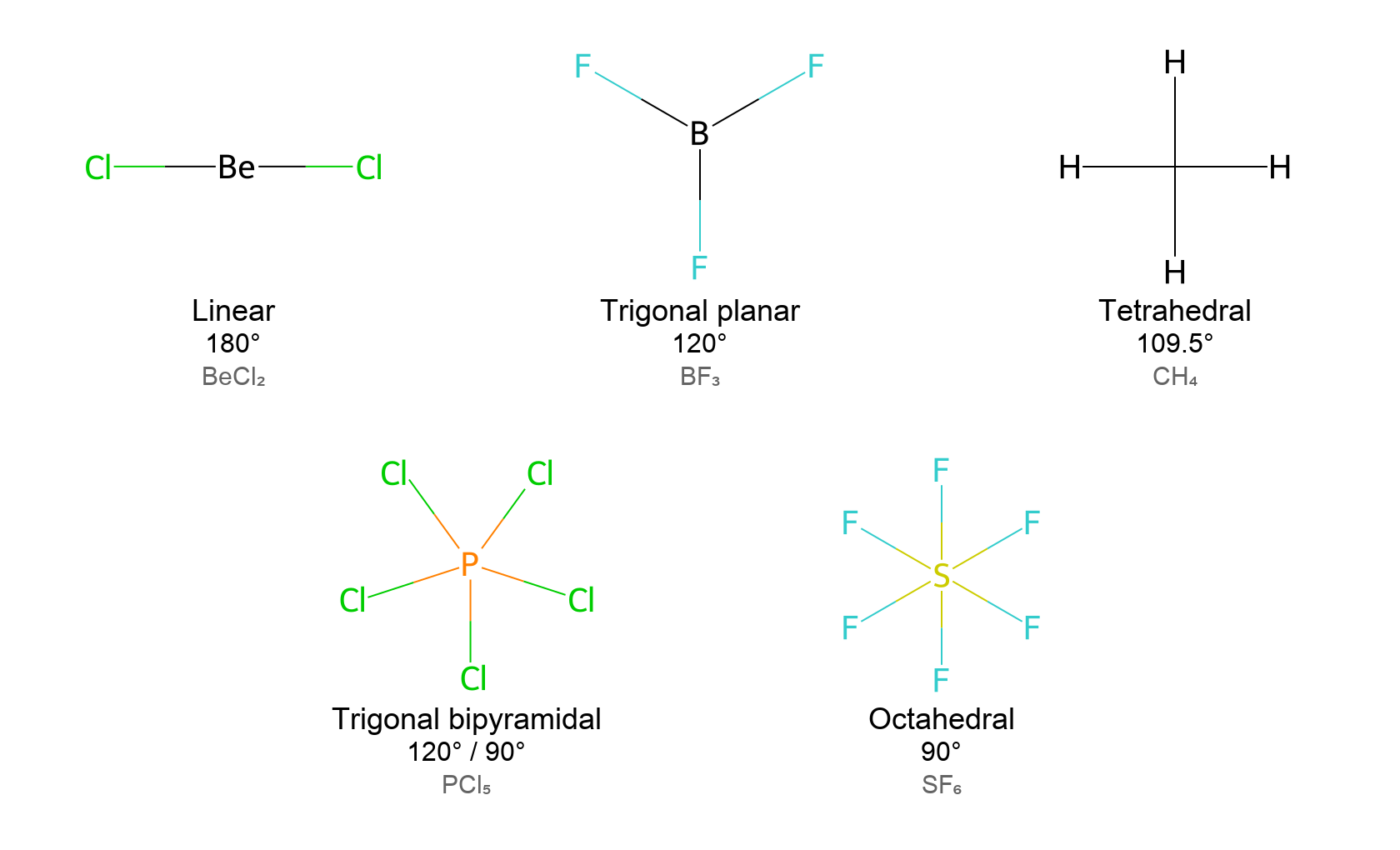

Electron Groups and Basic Geometries

VSEPR theory considers electron groups around the central atom. An electron group can be a single bond, double bond, triple bond, or a lone pair of electrons – each counts as one region of electron density. The total number of electron groups (also known as the steric number) dictates the ideal electron-pair geometry:

- 2 electron groups: Linear arrangement, with a bond angle of 180°. Example: BeCl₂ (beryllium chloride) is linear.

- 3 electron groups: Trigonal planar arrangement, with bond angles of 120°. Example: BF₃ (boron trifluoride) is trigonal planar.

- 4 electron groups: Tetrahedral arrangement, with bond angles of approximately 109.5°. Example: CH₄ (methane) is tetrahedral.

- 5 electron groups: Trigonal bipyramidal arrangement, with bond angles of 120° in the equatorial plane and 90° between axial and equatorial positions. Example: PCl₅ (phosphorus pentachloride) is trigonal bipyramidal.

- 6 electron groups: Octahedral arrangement, with 90° bond angles. Example: SF₆ (sulfur hexafluoride) is octahedral.

Organic molecules primarily involve carbon, which is usually tetravalent (4 electron groups), so tetrahedral, trigonal planar, or linear geometries are most common for carbon centers. For instance, a carbon with four single bonds is tetrahedral, a carbon with one double bond (and two single bonds) is trigonal planar, and a carbon with a triple bond (and one single bond) is linear.

Molecular Geometry vs. Electron Geometry

It is important to distinguish between electron-pair geometry (the arrangement of all electron groups around the central atom) and molecular geometry (the arrangement of only the atoms in space, ignoring lone pairs). Lone pairs occupy space and influence bond angles, but they are not visible as "bonded atoms" when describing molecular shape.

For example, consider ammonia (NH₃):

- Nitrogen has 4 electron groups (3 bonding pairs to H and 1 lone pair). Electron-pair geometry is tetrahedral (because 4 groups).

- Molecular geometry is trigonal pyramidal: the three hydrogen atoms define a base of a pyramid with nitrogen at the apex. The lone pair is not counted as a part of the molecular shape description, although it pushes the N–H bonds slightly closer together, reducing the H–N–H bond angle from the ideal 109.5° to about 107°.

Similarly, water (H₂O) has 4 electron groups (2 bonding pairs to H, 2 lone pairs). Electron-pair geometry is tetrahedral, but molecular geometry is bent, with an H–O–H bond angle of about 104.5° due to the repulsion of the two lone pairs.

Molecular geometry: trigonal pyramidal (~107°) for NH₃.

Molecular geometry: bent (~104.5°) for H₂O.

Lone-Pair Effects and Bond Angles

Lone pairs occupy slightly more space than bonding pairs. As lone pairs replace bonding pairs, bond angles compress in a predictable order:

- Tetrahedral (no lone pairs): 109.5° (CH₄)

- Trigonal pyramidal (one lone pair): ~107° (NH₃)

- Bent (two lone pairs): ~104.5° (H₂O)

Similarly, trigonal bipyramidal geometries place lone pairs in the equatorial positions first (seesaw, T-shaped, linear) to minimize 90° interactions. Use this pattern to rationalize distorted geometries in molecules such as SF₄ (seesaw) or ClF₃ (T-shaped).

Polarity and AXE Notation

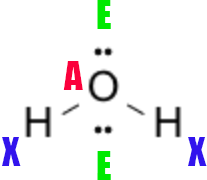

The AXE shorthand summarizes electron-domain counts:

- A = central atom

- X = number of atoms bonded to the central atom

- E = number of lone pairs on the central atom

For example, water is AX₂E₂ (electron geometry tetrahedral, molecular geometry bent), while BF₃ is AX₃E₀ (trigonal planar). After you identify the shape, assess whether dipoles cancel. Symmetric geometries (linear CO₂, trigonal planar BF₃, tetrahedral CCl₄) are often nonpolar, whereas asymmetric ones (bent H₂O, trigonal pyramidal NH₃) carry a net dipole.

Summary

- Count electron groups to determine electron geometry; then remove lone pairs from the description to name the molecular geometry.

- Lone pairs compress bond angles: tetrahedral → trigonal pyramidal → bent is the standard example.

- Use AXE notation plus symmetry arguments to predict polarity and compare molecules across a chapter.

The Role of Lone Pairs and Multiple Bonds

Lone pairs exert greater repulsive force than bonding pairs because they are localized closer to the nucleus. This increases repulsion and can compress bond angles:

- In ammonia (NH₃), the lone pair pushes the N–H bonds slightly closer, reducing the bond angle to ~107°.

- In water (H₂O), two lone pairs compress the bond angle even further to ~104.5°.

Multiple bonds (double or triple bonds) are also regions of higher electron density than single bonds. They can repel other electron groups more strongly, slightly affecting bond angles, though this effect is usually less pronounced than that of lone pairs.

Common Molecular Geometries in Organic Chemistry

Although VSEPR covers a wide range of geometries, organic chemistry frequently involves:

- Linear (180°): Central atoms with 2 electron groups, as in alkynes (e.g., the carbon in acetylene, HC≡CH).

- Trigonal Planar (120°): Central atoms with 3 electron groups and no lone pairs, often seen in sp²-hybridized carbons (e.g., the carbon in formaldehyde, H₂C=O).

- Tetrahedral (~109.5°): Central atoms with 4 electron groups and no lone pairs, typical of sp³-hybridized carbons (e.g., methane, CH₄).

- Trigonal Pyramidal (~107°): Central atoms with 4 electron groups, one of which is a lone pair (e.g., ammonia, NH₃).

- Bent (~104.5°): Central atoms with 4 electron groups, two of which are lone pairs (e.g., water, H₂O).

VSEPR and Molecular Polarity

Molecular geometry influences whether a molecule is polar or nonpolar. A molecule is polar if it has a net dipole moment – an uneven distribution of electron density resulting in partial positive and negative ends.

- Symmetry Matters: Even if bonds are polar, a symmetrical geometry can cancel dipole moments, resulting in a nonpolar molecule. For example, carbon dioxide (CO₂) is linear and symmetrical; the two polar C=O bonds cancel, making CO₂ nonpolar.

- Asymmetry Leads to Polarity: If polar bonds are arranged asymmetrically, the dipoles do not cancel, and the molecule is polar. For example, water (H₂O) is bent; its polar O–H bonds add to give a net dipole, making water polar.

Understanding both bond polarity and molecular geometry is key to predicting a molecule’s overall polarity, which affects solubility, boiling points, and interactions with other molecules.

Summary

VSEPR theory predicts molecular shapes based on minimizing electron pair repulsions around a central atom. Counting electron groups determines electron-pair geometry; considering only bonded atoms (and accounting for the greater repulsion of lone pairs and multiple bonds) gives molecular geometry and adjusted bond angles. Common shapes in organic chemistry include linear, trigonal planar, tetrahedral, trigonal pyramidal, and bent. Molecular geometry and bond polarity together determine whether a molecule is polar or nonpolar, influencing its physical and chemical behavior.