Carbonyl → Acetals/Thioacetals (ROH, RSH, Diols, Dithiols)

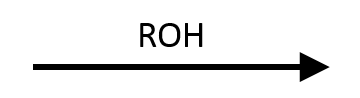

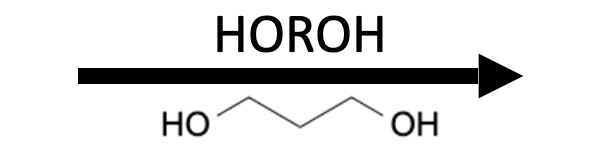

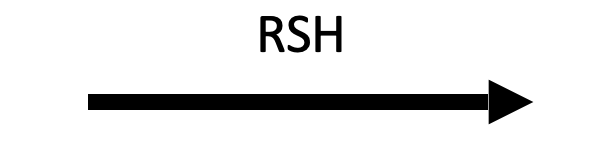

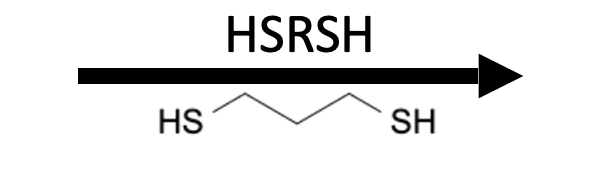

Aldehydes and ketones react reversibly with alcohols (ROH) under Brønsted acid catalysis to give acetals/ketals (two OR groups on the former carbonyl carbon) and with thiols (RSH) under Brønsted or Lewis acid catalysis to give thioacetals/thioketals (two SR groups). Diols (HO–R–OH) and dithiols (HS–R–SH) create five‑ and six‑membered cyclic (thio)acetals used as protecting groups. Water removal (Dean–Stark or sieves) pushes equilibria toward products; aqueous acid hydrolyzes back to the carbonyl. Diols/dithiols are reagents for cyclic protection not products themselves.

Quick Summary

- Buttons/modes: (1) Carbonyl + ROH (acetal/ketal), (2) Carbonyl + RSH (thioacetal), (3) Carbonyl + HO–R–OH (cyclic acetal), (4) Carbonyl + HS–R–SH (cyclic thioacetal).

- Catalysts: p‑TsOH, H₂SO₄, or BF₃·OEt₂/ZnCl₂ for RSH; keep acidic but not overly oxidizing for thiols.

- Driving force: Remove water (Dean–Stark or 3 Å/4 Å sieves); otherwise the equilibrium stops at the hemiacetal/hemithioacetal.

- Reversibility: Aqueous acid hydrolyzes acetals rapidly; thioacetals are more acid resistant and often require Hg²⁺/I₂ or Raney Ni (Mozingo) to undo.

- Protecting-group logic: Cyclic (thio)acetals from diols/dithiols are robust protecting groups against base/nucleophiles; thioacetals can also be reduced to methylene (umpolung toolkit).

Representation note: bromide is shown when labeling the Lewis-acid/BF₃·OEt₂ activation overlay solely for illustration; any halide or sulfonate that accompanies the catalyst behaves analogously.

Mechanism — Acid/Lewis-Acid Catalyzed Path (8 Steps)

Every mode shares the same polar spine: acid (or BF₃·OEt₂/ZnCl₂) activates the carbonyl, a nucleophile adds to give a (thio)hemiacetal, the hemi-OH is protonated so it can depart, the resulting oxonium collapses, the second heteroatom attacks, and mild workup deprotonates. Diols/dithiols simply perform Steps 3, 5, and 6 intramolecularly.

Mechanistic Checklist (Exam Focus)

- Aldehydes react faster than ketones (lower steric/EWG penalty). Cyclic closures help sluggish ketones by raising effective concentration.

- Acid catalysis is mandatory; base rarely works because dehydration is disfavored.

- Acetals/ketals are acid-labile/base-stable protecting groups; thioacetals are even more robust (plan hydrolysis or Raney-Ni desulfurization).

- Five- and six-member cyclic (thio)acetals are preferred; others are entropically disfavored.

- Water removal is required to go past the hemiacetal.

- The entire path is closed-shell; do not draw rearranging carbocations.

Worked Examples

Reactant

Reagents

Product

Reactant

Reagents

Product

Reactant

Reagents

Product

Reactant

Reagents

Product

Scope & Limitations

- Best substrates: Aldehydes; unhindered ketones; cyclic closures with 5/6-member diols/dithiols.

- Slower: Sterically hindered ketones or carbonyls bearing strong EWGs; use Lewis acids or heat.

- Regiochemistry: Unsymmetrical ketones + diols may give regioisomeric cyclic acetals; choose the diol length accordingly.

- Hydrolysis: Acetals hydrolyze in aqueous acid. Thioacetals survive acid/base but need metal salts (Hg²⁺, I₂) or Raney Ni (Mozingo) to revert or reduce to CH₂.

- Functional-group tolerance: Avoid strongly oxidizing conditions when thiols are present; protect other acid-sensitive groups before acetalization.

Practical Tips & Pitfalls

- Dry solvents, Dean–Stark, or sieves are essential—no water removal means no acetal.

- Match catalyst to nucleophile: ROH → mild Brønsted acids (p‑TsOH, H₂SO₄); RSH/HS–R–SH often respond better to BF₃·OEt₂ or ZnCl₂.

- For protecting groups, cyclic acetals (ethylene glycol) are more robust than acyclic; cyclic thioacetals withstand even harsher conditions.

- Control odor and oxidation when using thiols (work under N₂/Ar, quench waste with bleach).

- Plan the endgame: acetals unmask via aq. acid, whereas thioacetals can be leveraged for Mozingo (Raney Ni → CH₂).

Exam-Style Summary

Carbonyl + ROH (acid, −H₂O) → acetal/ketal. Carbonyl + RSH (acid/BF₃·OEt₂, −H₂O) → thioacetal. Diols/dithiols deliver cyclic protecting groups (5/6-member). The mechanism is reversible: protonate carbonyl → (thio)hemiacetal → activate OH → lose H₂O → capture → deprotonate. Remove water to drive forward; add water/acid to unmask. Thioacetals are more acid-resistant and can be desulfurized (Mozingo) to CH₂.

Interactive Toolbox

- Mechanism Solver — choose the ROH, RSH, HO–R–OH, or HS–R–SH buttons to watch the 4-mode spine (activate → hemi → oxonium → capture).

- Reaction Solver — compare aldehydes vs ketones and diol/dithiol options to predict acyclic vs cyclic products.

- IUPAC Namer — generate names for cyclic protecting groups such as 1,3-dioxolanes and 1,3-dithianes.

Related Reading

- Carbonyl + Amine Condensation → Imines/Enamines — another equilibrium-driven carbonyl derivatization under acid catalysis.

- Gilman (R₂CuLi) Conjugate Addition — complementary “soft” nucleophile chemistry where protecting the carbonyl might be necessary before organometallic steps.

FAQ

Do acetals form under basic conditions? No. The dehydration step requires acid; base typically stalls at the hemiacetal.

Why use a diol/dithiol instead of two equivalents of ROH/RSH? Diols/dithiols create intramolecular attacks that favor five- or six-member rings, giving robust cyclic protecting groups.

How do I remove a cyclic acetal? Aqueous acid (often dilute HCl, H₂SO₄, or p‑TsOH in MeOH/H₂O) hydrolyzes acetals back to the carbonyl and diol.

How do I unmask a thioacetal? Thioacetals resist simple acid hydrolysis; Hg²⁺/H₂O, I₂/H₂O, or Raney Ni (Mozingo reduction to CH₂) are common strategies.

Why are thioacetals useful beyond protection? They can invert polarity (umpolung) and, upon Raney Ni treatment, reduce a carbonyl to CH₂ in two steps.