Drawing Organic Structures (Structural Formulas)

Drawing Organic Structures (Structural Formulas)

Organic molecules can be represented in multiple ways, each with a different level of detail and clarity. As molecules grow larger and more complex, drawing every atom can become cumbersome, so chemists use various structural formulas and shorthand notations to simplify diagrams while conveying the essential information.

The three common representations are:

- Lewis structures (full structural formulas)

- Condensed formulas

- Line-angle (skeletal) formulas

Understanding these conventions is important for reading and writing organic chemistry structures.

Lewis (Full) Structural Formulas

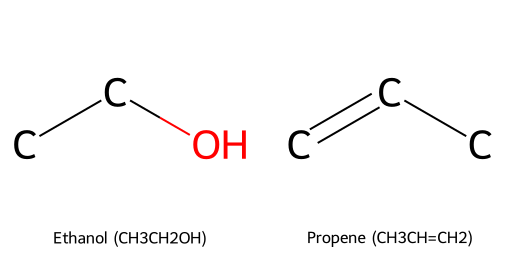

Lewis structures or full structural formulas show all atoms in a molecule and all bonds (as lines) between them. For example, ethanol can be drawn as:

In this full structure:

- Each carbon (C) and oxygen (O) is explicitly shown.

- Every bond (single line for single bonds, double line for double bonds, etc.) is drawn between atoms.

- All hydrogen (H) atoms are drawn and attached to the atom they are bonded to.

Lewis structures are useful for small molecules or for teaching fundamental concepts like bonding and lone pairs. However, for larger molecules, they become cluttered.

Condensed Structural Formulas

A condensed formula streamlines the Lewis structure by omitting some or all bond lines and grouping atoms together. It lists atoms in a sequential order that indicates how they are connected, often grouping hydrogen atoms with the carbon to which they are attached.

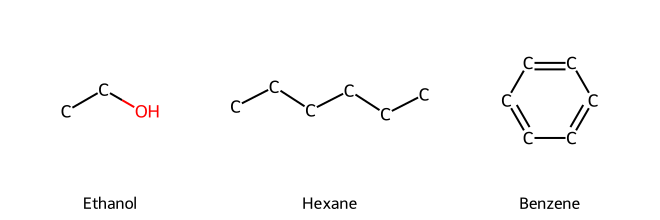

For example, the condensed formula for ethanol (CH₃CH₂OH) can be written as CH₃CH₂OH. This indicates:

- A CH₃ group (a carbon with 3 hydrogens) attached to

- a CH₂ group (a carbon with 2 hydrogens) attached to

- an OH group (oxygen with hydrogen, indicating an alcohol).

Other examples:

- n-Butane (C₄H₁₀) can be condensed as CH₃CH₂CH₂CH₃.

- Propene (C₃H₆ with a double bond) might be written as CH₃CH=CH₂ (indicating a double bond between the second and third carbon).

Condensed formulas save space and are often used in text or linear lists, but they still explicitly show the molecular formula and connectivity.

Line-Angle (Skeletal) Formulas

Line-angle formulas (also called skeletal structures or bond-line notation) are the most abbreviated and are heavily used in organic chemistry. In this format:

- Carbon atoms are not drawn explicitly as a "C"; instead, a carbon is implied at each vertex (corner) or line terminus.

- Hydrogen atoms bonded to carbon are omitted entirely; they are assumed to be present to fulfill carbon’s valence (each carbon makes 4 bonds).

- Lines represent bonds between carbons. Single lines for single bonds, double lines (double bonds), triple bonds shown by three parallel lines or an equals sign with an extra line.

- Heteroatoms (atoms other than C and H, like O, N, Cl, etc.) are explicitly shown, and any hydrogens attached to heteroatoms are shown.

For instance, the line-angle representation of ethanol would be drawn as two line segments: a zigzag with one end labeled "OH". Specifically, a line connecting two vertices (each vertex representing a carbon) and at the end of the line, an "OH" group attached to the second carbon's vertex. Alternatively, since ethanol is small, it might be drawn with an explicit "CH₃CH₂OH" in skeletal form where the carbon atoms are implied.

Another example is hexane (C₆H₁₄). In line-angle form, hexane is drawn as a simple zigzag line with six vertices or ends (since a straight chain of six carbons will have a zigzag shape due to tetrahedral bond angles).

Key points for reading skeletal structures:

- A vertex or line terminus is a carbon with appropriate number of hydrogens (to make 4 bonds total).

- Multiple bonds are shown clearly (e.g., an alkene is a double line).

- Charges or lone pairs, if relevant (like on an oxygen or a carbocation), should be indicated.

- If a carbon has a formal charge or an explicit lone pair (as in a carbocation or carbanion), it can be drawn and labeled with the charge.

Skeletal structures are very efficient for complex molecules. Benzene, for example, is drawn as a hexagon with alternating double bonds (or a hexagon with a circle inside to denote aromaticity) instead of writing out each carbon and hydrogen.

Wedge-and-Dash Notation for 3D Perspective

Sometimes line-angle drawings include wedge-and-dash notation to indicate 3-dimensional arrangement:

- A solid wedge indicates a bond coming out of the plane toward the viewer.

- A hashed (dashed) wedge indicates a bond going back behind the plane.

- A normal line remains in the plane of the page/screen.

For example, a tetrahedral carbon (such as in CH₄ or in many sp³ centers) is often drawn with one wedge bond, one dashed bond, and two normal lines to convey the 3D shape.

This notation becomes important when discussing stereochemistry (the 3D arrangement of substituents), such as distinguishing enantiomers. However, even in basic structure drawings, wedge/dash notation helps clarify geometry (like showing the shape of molecules or specific spatial arrangements in a cyclic structure).

Summary

Organic structures can be depicted at different levels of detail. Lewis structures show all atoms and bonds explicitly, which is useful for small molecules and learning fundamentals. Condensed formulas provide a linear shorthand that indicates connectivity without drawing every bond. Line-angle (skeletal) formulas are the standard for complex structures, omitting carbon symbols and C–H bonds entirely, and using vertices and lines to represent the carbon framework. Additionally, wedge-and-dash notation is used alongside these structures to indicate 3D geometry when needed. Being fluent in interpreting and drawing these representations is essential for communicating organic chemistry information efficiently.