Resonance and Delocalized Electrons

Resonance and Delocalized Electrons

Sometimes a single Lewis structure is insufficient to represent the true electron distribution in a molecule. Resonance describes delocalized electrons in systems where bonding cannot be captured by just one static Lewis structure. Instead, we draw multiple resonance contributors that differ only in electron placement, then remember the actual molecule is a hybrid of all valid contributors. Resonance is essential for understanding the stability, reactivity, and physical properties of conjugated organic molecules.

- What Is Resonance?

- Rules for Drawing Resonance

- Examples of Resonance in Organic Molecules

- Resonance and Reactivity

What Is Resonance?

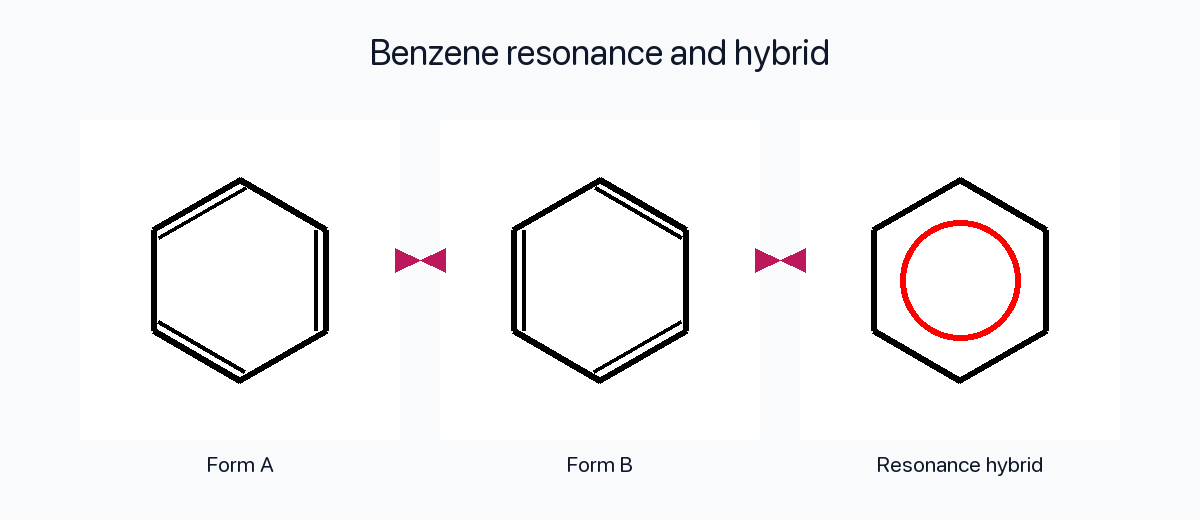

Resonance structures are alternative Lewis drawings that keep atom connectivity the same while shifting the placement of π electrons or lone pairs. The nitrate ion (NO₃⁻), for example, can be drawn with a double bond to any one of the three oxygens; experimentally, all three N–O bonds are equivalent because the real electron distribution is a resonance hybrid of those contributors. The same logic explains benzene: two Kekulé drawings show alternating double bonds, yet every C–C bond is identical because the six π electrons are delocalized around the ring.

Rules for Drawing Resonance

Each rule below is paired with an RDKit-rendered visual so you can see the idea in action.

Valid Lewis Structures

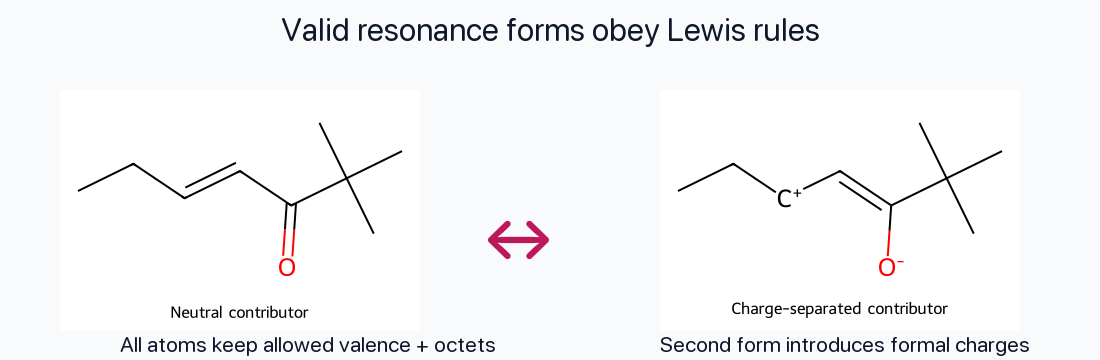

Every contributor must be a legitimate Lewis structure: correct valence electron count, proper formal charges, and octets for second-row atoms unless an accepted exception applies.

Atom Positions Fixed

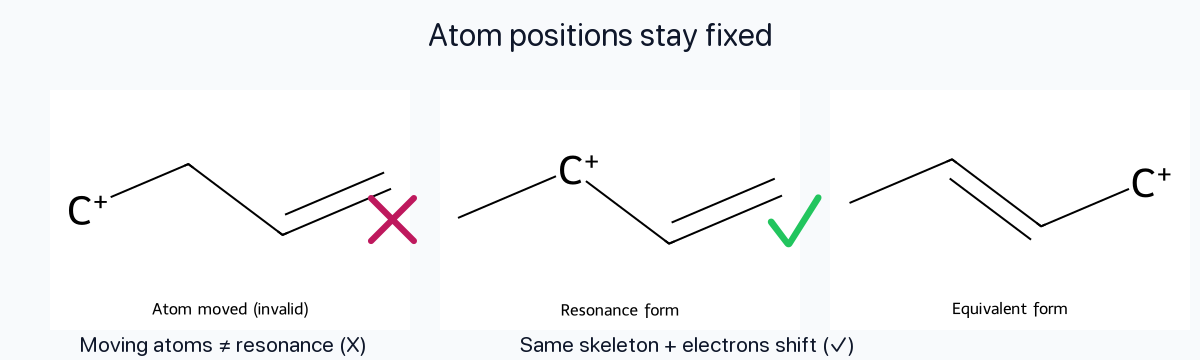

Only electrons move between contributors. The skeletal arrangement of atoms (the σ framework) never changes; otherwise you are drawing a different molecule, not a resonance form.

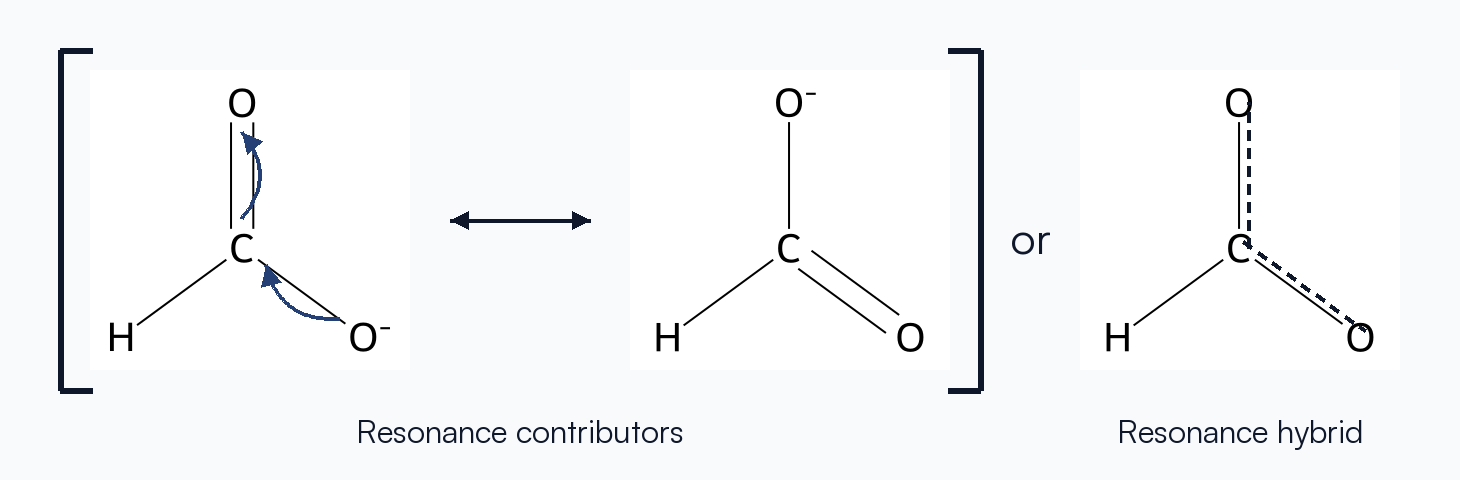

Curved Arrow Notation

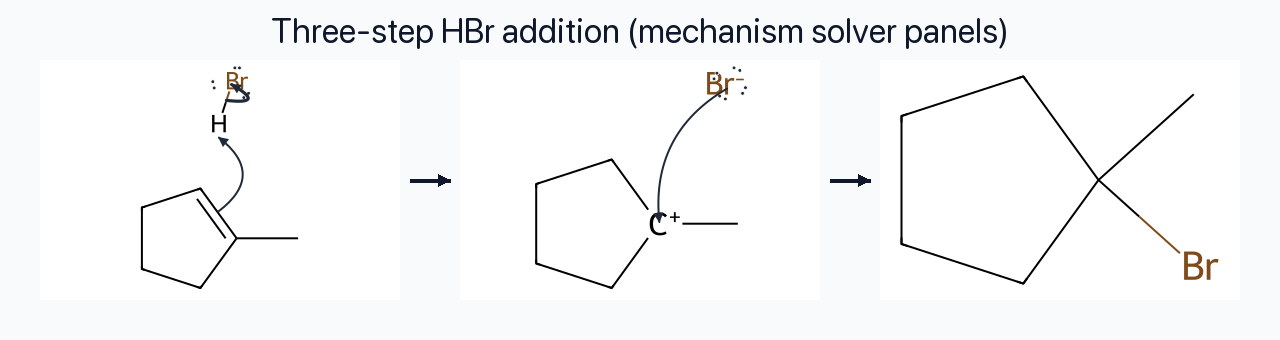

Curved arrows communicate how electrons shift from one contributor to the next. The tail always starts at an electron source (lone pair or bond) and the head points to where that pair lands.

Double-Headed Arrow Between Forms

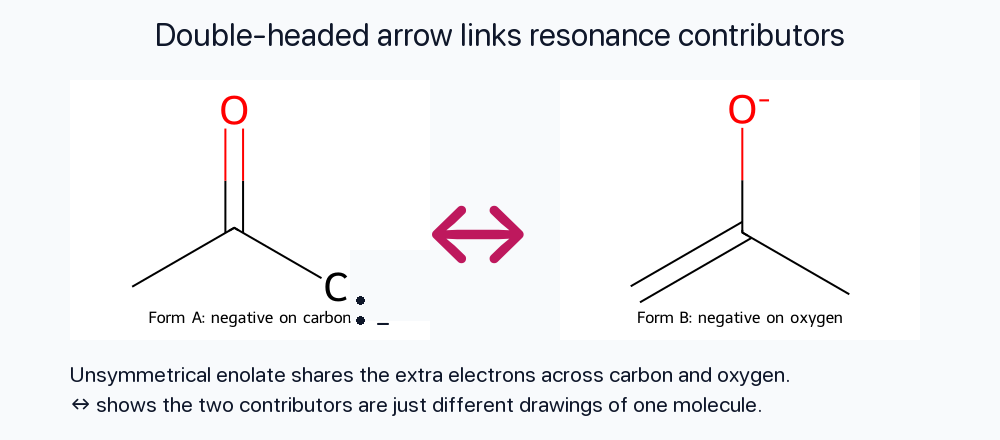

Contributors are connected with a double-headed arrow (↔) to emphasize that they are not isolable species—just different depictions of the same molecule.

Resonance Hybrid

The true structure is the weighted average of all valid contributors. Equivalent contributors (like the two Kekulé drawings of benzene) contribute equally; non-equivalent ones contribute according to their stability (best octets, minimal formal charge separation, negative charge on electronegative atoms, etc.).

Stability Implications

Delocalizing charge or π electrons lowers the overall energy. The more significant the contributors (and the greater their number), the larger the resonance stabilization.

Examples of Resonance in Organic Molecules

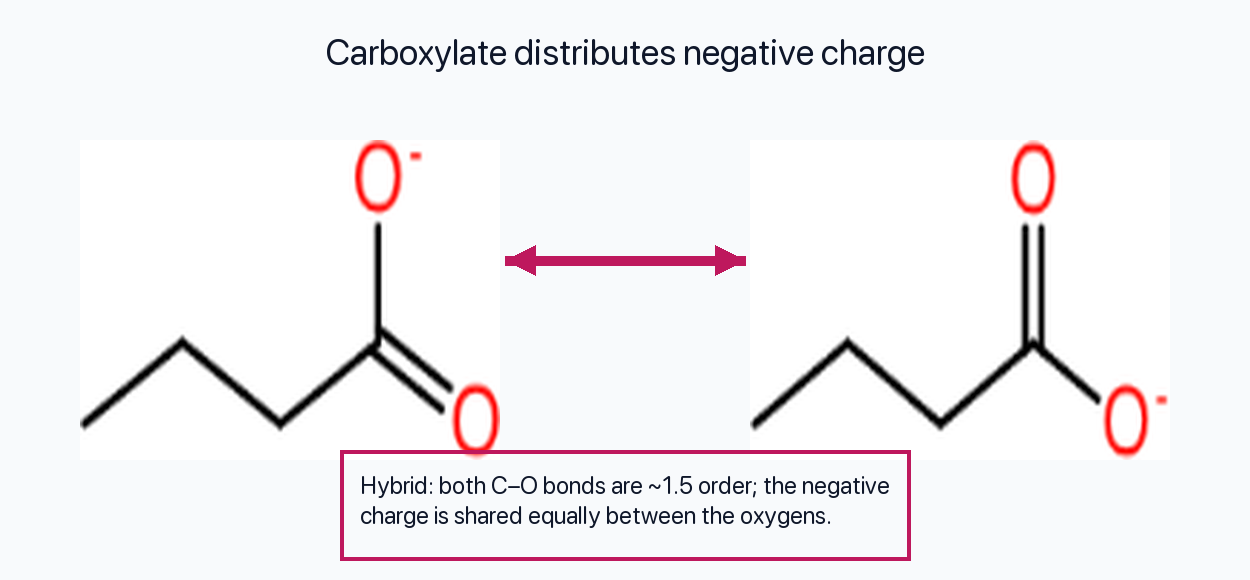

Carboxylate Ions (e.g., Acetate, CH₃COO⁻)

Two contributors place the C=O double bond on different oxygens. The resonance hybrid has two equivalent C–O bonds (≈1.5 bond order) and the negative charge is evenly shared between the two oxygens.

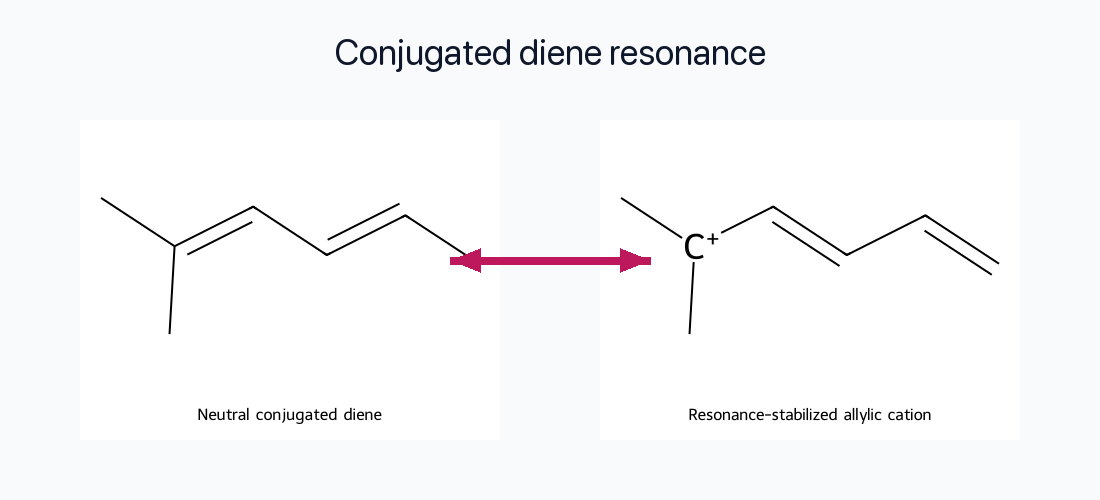

Allylic Cations and Anions

Allylic ions feature a p orbital adjacent to a π bond, allowing charge to delocalize to both terminal atoms. This stabilization explains the unusual reactivity of allylic intermediates in SN1, E1, and radical mechanisms.

Aromatic Systems

Every carbon in benzene participates in a cyclic array of overlapping p orbitals. The delocalized π cloud makes all six C–C bonds equivalent and delivers the extra stabilization we call aromaticity.

Conjugated Dienes

Even though 1,3-butadiene lacks two fully equivalent contributors, its conjugated π system allows charge and bond order to spread over multiple carbons. This delocalization becomes especially important in pericyclic reactions and excited states.

Resonance and Reactivity

Resonance strongly influences how molecules behave:

- Stabilized intermediates: Allylic, benzylic, and carbonyl-stabilized ions or radicals form more readily because their charge or radical character can delocalize.

- Electrophilicity and nucleophilicity: Carbonyls, nitro groups, and conjugated π systems can pull or push electron density via resonance, tuning reactivity at specific atoms.

- Aromatic substitution: Benzene and other aromatic rings prefer substitution over addition so that the aromatic π system—and its resonance energy—remains intact.

Recognizing possible resonance contributors is therefore a prerequisite to predicting mechanisms, regiochemistry, and product stability.

Summary

- Resonance contributors keep atom positions fixed while shifting electrons; only valid Lewis structures count.

- The real molecule is the resonance hybrid, usually more stable than any single contributor because charge and π density are delocalized.

- Delocalization explains key stability trends in carboxylates, allylic systems, aromatics, and conjugated dienes, directly influencing organic reaction pathways.