Alkane Nomenclature and Properties

Alkane Nomenclature and Properties

Alkanes and cycloalkanes are the simplest saturated hydrocarbons in organic chemistry.

- Alkanes contain only C–C single bonds in open chains (linear or branched).

- Cycloalkanes are ring analogues composed of C–C single bonds arranged in a cycle.

Both families follow systematic IUPAC nomenclature and display predictable physical property trends that depend on chain length, branching, and ring size.

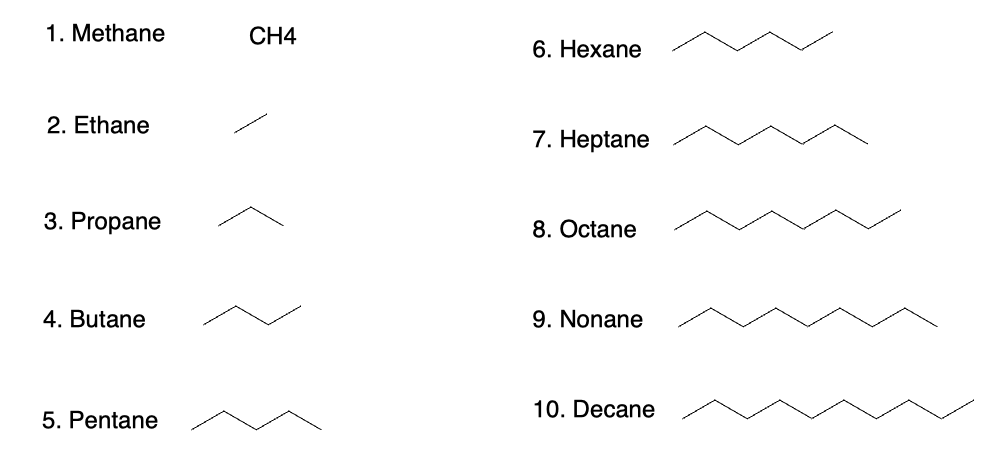

1. IUPAC Nomenclature of Unbranched Alkanes

Unbranched (normal) alkanes are named by combining:

- A prefix indicating the number of carbons

- The suffix

-anefor a saturated hydrocarbon

Common prefixes:

meth-→ methane (CH₄, 1 carbon)eth-→ ethane (C₂H₆, 2 carbons)prop-→ propane (C₃H₈, 3 carbons)but-→ butane (C₄H₁₀, 4 carbons)pent-,hex-,hept-,oct-, etc. for longer chains

For an unbranched chain, the parent name is simply the carbon count + -ane.

2. Branched Alkanes: Parent Chain and Substituents

Most structures in organic chemistry are branched alkanes, requiring a few additional rules.

2.1 Parent-chain selection

- Identify the longest continuous carbon chain; this is the parent.

- If multiple chains of equal length exist, choose the one with:

- The greatest number of substituents, or

- The highest-priority substituent pattern according to standard IUPAC tie‑breakers.

The parent chain name uses the same prefixes as unbranched alkanes (e.g. hexane, heptane).

2.2 Substituent naming and numbering

Side chains are treated as alkyl substituents:

- Replace

-anewith-yl:- CH₃– → methyl

- CH₃CH₂– → ethyl

- CH₃CH₂CH₂– → propyl, etc.

Number the parent chain so that:

- The first point of difference rule is satisfied: the lowest possible set of locants is obtained for substituents.

- If there is still a tie, the substituent that comes alphabetically first receives the lower locant.

Multiple identical substituents use the prefixes di-, tri-, tetra-, etc., but these multiplying prefixes are not considered in alphabetical ordering.

Example: 2-methylpentane

- Longest chain: 5 carbons → pentane

- Substituent: CH₃– (methyl) on carbon 2 → 2-methyl

- Full name: 2-methylpentane

3. Additional Features in Alkane Naming

A few further points are commonly emphasized in introductory courses:

-

Multiple different substituents:

List substituents in alphabetical order (ignoring di-, tri-, sec-, tert-, etc.) with their locants. Example:

3-ethyl-2-methylhexane(ethyl before methyl). -

Complex substituents (branched alkyl groups):

Draw the substituent, choose its own “mini parent” chain, and name it in parentheses with its own numbering, e.g.(1-methylethyl)for isopropyl, depending on how strictly your course enforces modern IUPAC naming. -

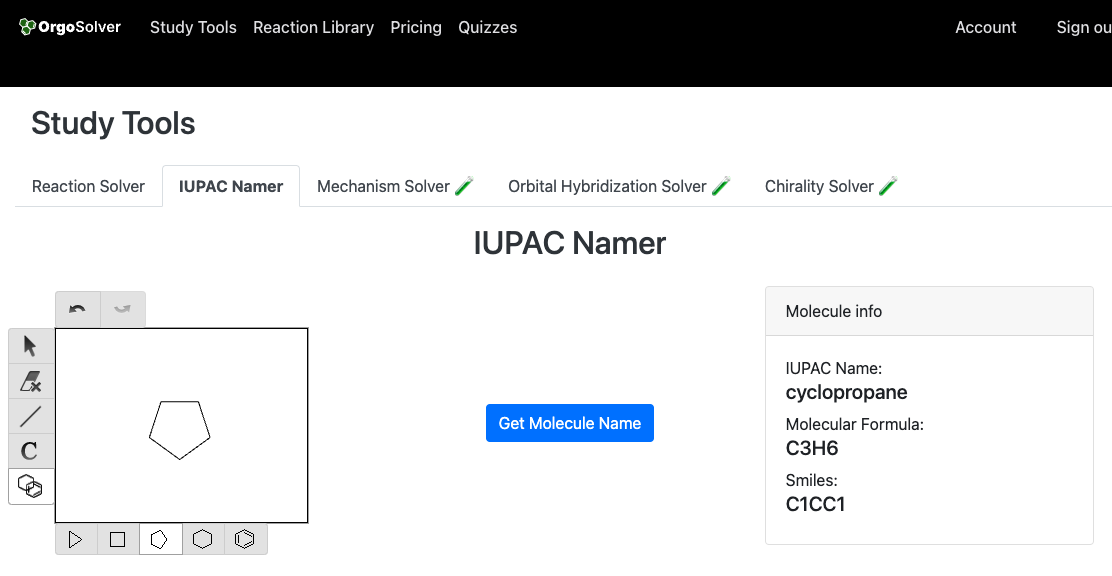

Use of IUPAC Namer:

Structures can be drawn and checked using the IUPAC Namer to reinforce these rules.

4. Physical Properties of Alkanes

Alkanes are nonpolar molecules dominated by London dispersion forces, so their physical properties follow simple trends:

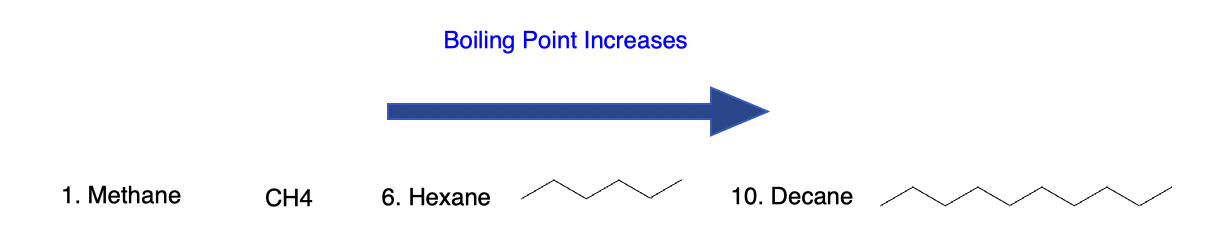

4.1 Boiling points and chain length

- As chain length increases, surface area increases and dispersion forces strengthen.

- This leads to higher boiling points for longer alkanes at a given pressure.

For example, methane is a gas at room temperature, hexane is a liquid, and very long-chain alkanes can be waxy solids.

4.2 Effect of branching

- More branching lowers the surface area compared with a straight chain of the same formula.

- This generally lowers the boiling point (branched alkanes pack less efficiently and have weaker dispersion interactions).

4.3 Solubility and density

- Alkanes are insoluble in water but soluble in many nonpolar or weakly polar organic solvents.

- Their densities are typically less than that of water, so they float on aqueous layers.

4.4 Chemical inertness

- C–C and C–H σ bonds are relatively strong and nonpolar.

- Under ordinary conditions alkanes are chemically unreactive, apart from:

- Combustion: complete oxidation to CO₂ and H₂O

- Radical halogenation under light/heat (e.g. chlorination or bromination)

These features justify the description of alkanes as “paraffins” (little affinity) in older terminology.

5. Nomenclature of Cycloalkanes

Cycloalkanes are saturated hydrocarbons in which the carbon atoms form a ring.

5.1 Parent name and numbering

- Parent name:

cyclo+ alkane name, e.g.- cyclopropane (3‑membered ring)

- cyclobutane (4)

- cyclopentane (5)

- cyclohexane (6), etc.

Numbering rules:

- For a monosubstituted cycloalkane (e.g., methylcyclohexane), the substituent is understood to be at carbon 1; the “1” is often omitted in simple names.

- For disubstituted or polysubstituted rings:

- Number the ring to give the lowest possible locants as a set.

- If there is a tie, choose the scheme where the substituent that is alphabetically first receives the lowest number.

Example:

A ring with ethyl and methyl substituents would be numbered so that ethyl (alphabetically earlier) has the lower locant if possible.

5.2 Ring vs chain as parent

When a ring is attached to a much longer alkyl chain, some textbooks treat the longer chain as the parent alkane and the ring as a cycloalkyl substituent. Course expectations vary; students should follow the convention used in their text or instructor examples.

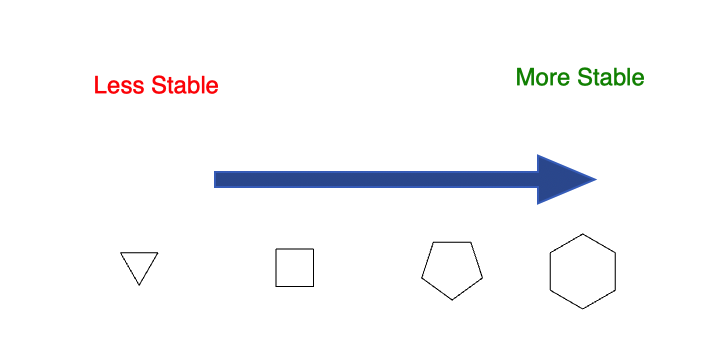

6. Ring Strain and Properties of Cycloalkanes

Cycloalkanes share many physical properties with their acyclic analogues (nonpolarity, dispersion forces), but their ring geometry introduces ring strain.

6.1 Sources of ring strain

Ring strain can include:

- Angle strain: deviation of bond angles from the ideal tetrahedral angle (109.5°) of sp³ carbons.

- Torsional strain: eclipsing interactions between neighboring C–H bonds.

- Transannular (steric) strain: nonbonded interactions across a ring in larger rings.

Trends (approximate qualitative picture):

-

Cyclopropane, cyclobutane:

Significant angle and torsional strain; relatively high energy and more reactive in ring‑opening reactions. -

Cyclopentane, cyclohexane:

Can adopt nonplanar conformations (e.g., envelope for cyclopentane, chair for cyclohexane) that greatly relieve strain.

Cyclohexane in a chair conformation is often treated as a nearly strain‑free reference. -

Larger rings (≥ C₇):

Can accommodate near‑tetrahedral bond angles, but may develop transannular interactions; strain depends on specific conformation.

6.2 Physical properties

- Boiling points of cycloalkanes are often slightly higher than those of acyclic alkanes with similar carbon count, due to the more compact shape and somewhat stronger London forces.

- Cycloalkanes are similarly nonpolar and insoluble in water, but dissolve in typical organic solvents.

6.3 Reactivity and ring-opening

Small, highly strained cycloalkanes (especially three‑ and four‑membered rings) are more susceptible to:

- Hydrogenation (relieving strain)

- Halogenation or addition reactions that break the ring

- In biosynthesis/biochemistry, enzyme‑mediated ring openings can exploit strain for reactivity.

Summary

- Alkanes (acyclic) and cycloalkanes are saturated hydrocarbons; all carbons are sp³ with ~109.5° bond angles.

- IUPAC naming: find the longest chain, number for lowest locants, name and alphabetize substituents; cycloalkanes use “cyclo-” parent and similar numbering rules.

- Physical properties: nonpolar, low-density, insoluble in water; boiling points rise with chain length and fall with branching. Cycloalkanes can show slight differences and ring-strain-dependent reactivity.