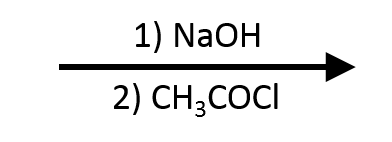

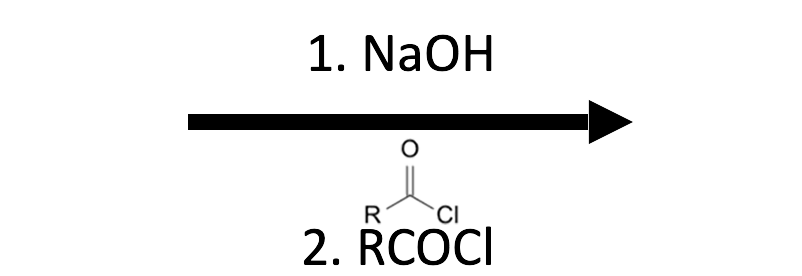

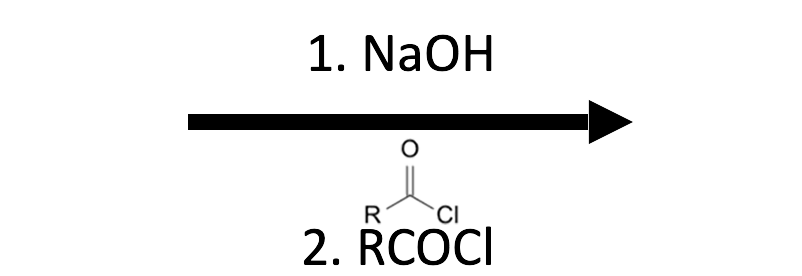

Carboxylic Acid → (Acetic / Mixed) Anhydride with NaOH then CH₃COCl

Treating a carboxylic acid with NaOH generates its carboxylate salt, a strong nucleophile that rapidly attacks acetyl chloride. Collapse of the tetrahedral intermediate ejects chloride to produce a mixed acetic anhydride (RCO₂COCH₃). When R = CH₃, both acyl fragments are acetyl and the product is symmetrical acetic anhydride.

Quick Summary

| Reagents / conditions | Step 1: NaOH (1.0 eq) or any strong base to form RCO₂⁻ Na⁺. Step 2: CH₃COCl (≈1 eq, slight excess) added in a dry aprotic solvent (Et₂O, CH₂Cl₂, THF) at 0–25 °C. |

|---|---|

| Outcome | RCO₂H → RCO₂COCH₃ (mixed acetic anhydride) + NaCl + H₂O. If R = CH₃, product is acetic anhydride. |

| Mechanism | Base deprotonation → carboxylate attack on acetyl chloride → tetrahedral intermediate collapse ejecting Cl⁻ → anhydride formation. |

| Key pivot | The nucleophile is the carboxylate oxygen, not the neutral acid. Mixed anhydride retains the original carbonyl and adds an acetyl fragment. |

| When it fails | Water during step 2 hydrolyzes CH₃COCl; trace base must be consumed before acylation so the acid chloride survives long enough to react. |

Mechanism — Three RDKit Frames + Product

Mechanistic Checklist (Exam Focus)

- Always show the base-generated carboxylate before the acetyl chloride step.

- The mechanism is nucleophilic acyl substitution: attack → tetrahedral intermediate → collapse expelling Cl⁻.

- The original carbonyl remains untouched; the new acetyl group is appended through the carboxylate oxygen.

- Symmetric acetic anhydride appears only when the starting acid is acetic acid.

- Water must be excluded during step 2 to prevent rapid hydrolysis of CH₃COCl.

- Draw NaCl (or at least Cl⁻) as an inorganic by-product; it helps justify the need for base.

Worked Examples

Example 1 — Ethanoic acid → Ethanoic anhydride

Both halves are acetyl (ethanoyl); the teal highlight tracks one CH₃CO fragment that originated from the base-activated acid.

Symmetric outcome: the carboxylate and acetyl chloride fragments are identical, so the solver labels the product “ethanoic anhydride.”

Example 2 — Benzenecarboxylic acid → Benzoyl ethanoic anhydride

The highlight follows the benzoyl fragment; acetyl chloride delivers the non-highlighted acetyl half to form benzoyl ethanoate anhydride.

This mixed anhydride is often used as an activated acyl donor for peptide couplings or Friedel–Crafts benzoylations.

Example 3 — Dodecanoic acid → Dodecanoyl ethanoic anhydride

The teal highlight tracks the dodecanoyl fragment; the acetyl piece is left uncolored for clarity.

Long-chain mixed anhydrides are common acylating agents for selective esterifications or peptide couplings.

Scope & Limitations

- Good substrates: Primary and secondary aliphatic acids, benzoic/aryl acids, α,β-unsaturated acids (though they can acylate at carbonyl more slowly).

- Challenging substrates: Highly hindered acids react sluggishly; β-dicarbonyl acids can decarboxylate under basic conditions.

- Moisture sensitivity: Step 2 demands anhydrous conditions; acetyl chloride hydrolyzes faster than the desired substitution if water persists.

- Mixed anhydride reactivity: Products are electrophilic and may react with any nucleophile still present (alcohols, amines, thiols).

- Thermal stability: Mixed anhydrides can decompose on heating; isolate promptly or carry forward in situ for coupling chemistry.

Practical Tips & Pitfalls

- Pre-form the sodium carboxylate, then transfer it (or its solution) into a dry flask before adding CH₃COCl.

- Add acetyl chloride slowly at low temperature to control exotherms and minimize side hydrolysis.

- Use inert atmosphere when possible; HCl fumes evolve and should be captured in a base trap.

- Wash the crude mixture with saturated NaHCO₃ to remove residual acetic acid once acylation is complete.

- If a pure mixed anhydride is not required, it can be used immediately in downstream acylations (amide/ester formation).

Exam-Style Summary

RCO₂H --(NaOH)--> RCO₂⁻ Na⁺ --(CH₃COCl)--> RCO₂COCH₃ + NaCl

Symmetric acetic anhydride forms only when R = CH₃. Mechanism = deprotonation + nucleophilic acyl substitution with chloride as the leaving group.

Interactive Toolbox

Use these study tools to connect the article back to the interactive apps:

- Mechanism Solver — pick either NaOH → CH₃COCl or NaOH → RCOCl, then replay the four RDKit frames (deprotonation, attack, collapse, product) with overlays.

- Reaction Solver — draw any carboxylic acid, apply NaOH then acetyl chloride, and confirm whether the solver labels the product “ethanoic anhydride” (R = Me) or “mixed acetic anhydride.”

- IUPAC Namer — verify systematic names such as “ethanoic anhydride” or “benzoyl ethanoic anhydride” without copying SMILES.

FAQ / Exam Notes

Why not attack with the neutral acid?

The conjugate base is far more nucleophilic. Showing RCO₂⁻ clarifies that chloride is displaced, not hydroxide.

Is this an esterification?

No. Anhydrides have two acyl groups joined by oxygen (RCO–O–COR′). Esters possess alkoxy substituents (RCO–OR′).

What if water sneaks in?

Acetyl chloride hydrolyzes to acetic acid, consuming the reagent and preventing anhydride formation. Dry glassware and solvents are mandatory in step 2.

Can other acid chlorides be used?

Yes. Replacing CH₃COCl with another R′COCl yields a general mixed anhydride RCO₂COR′. The “carboxy_naoh_rcocl” button in the Mechanism Solver mirrors that variant.

How do I know the product is “mixed”?

If the starting acid is not acetic acid, just highlight the fragment that came from the original acid; the other half is acetyl. Labeling it as “mixed acetic anhydride” is acceptable on exams.

Related Reading

- Carboxylic Acid → Acid Chloride with SOCl₂ — upstream activation step when acetyl chloride is not directly available.

- Amide Formation from Carboxylic Acids using DCC — another strategy for turning carboxylates into activated acyl donors (O-acylisourea vs mixed anhydride).