Hell–Volhard–Zelinsky Reaction — Carboxylic Acid → α‑Halo Acid

The Hell–Volhard–Zelinsky (HVZ) reaction selectively halogenates the α‑position of a carboxylic acid that possesses at least one α‑hydrogen. X₂ (Br₂ or Cl₂) and a phosphorus trihalide (PBr₃ or PCl₃, or red P + X₂) temporarily convert the acid into an acyl halide, which enolizes, undergoes electrophilic halogenation, and is hydrolyzed back to an α‑halo carboxylic acid.

Quick Summary

| Reagents / conditions | 1) X₂ + PX₃ (Br₂/PBr₃ or Cl₂/PCl₃) 2) H₂O workup. Often run neat or in CCl₄/CH₂Cl₂ with gentle heating. |

|---|---|

| Scope | Aliphatic carboxylic acids with ≥1 α‑H (RCH₂CO₂H or R₂CHCO₂H). No α‑H (e.g., benzoic acid, pivalic acid) → no HVZ. |

| Outcome | Replaces one α‑H with X to give RCHXCO₂H (typically α‑bromo or α‑chloro). Mono‑halogenation dominates under standard conditions. |

| Mechanistic highlights | Acid → acyl halide → enolization → electrophilic halogenation → hydrolysis. Halogenation happens on the acyl halide enol, not on the free acid. |

| Use cases | Access to α‑halo acids, which are versatile synthons for α‑substitutions (e.g., SN2 with NH₃ to form α‑amino acids). |

Mechanism — HVZ (Acyl Halide Enolization Pathway)

Mechanistic Checklist (Exam Focus)

- Activation matters: Show the acyl halide explicitly; halogenation does not occur directly on RCO₂H.

- Need an α‑H: No α‑H → no enolization → no HVZ product. Benzoic acid and t‑butanoic acid are common “no reaction” traps.

- Enol + X₂: Depict the enol of the acyl halide as the nucleophile; curved arrows remain closed‑shell (no radicals).

- Mono‑halogenation: The first halogen decreases enolization, so additional α‑halogenation is disfavored under standard conditions.

- Hydrolysis: Finish with the α‑halo carboxylic acid (not the acyl halide); include water workup in arrow-pushing problems.

Worked Examples

Propanoic acid → 2‑bromopropanoic acid

1) Br₂, PBr₃ 2) H₂O. The α‑CH₂ next to CO₂H loses one H and gains Br; the highlight marks only the α‑Br atom.

HVZ introduces a single Br at the α‑position; further bromination is strongly disfavored.

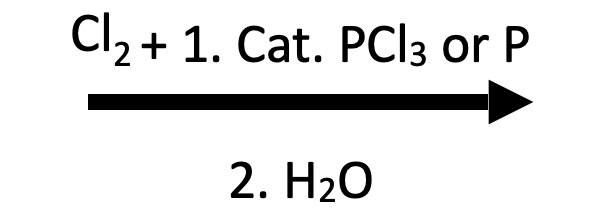

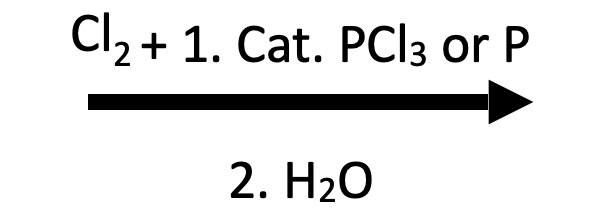

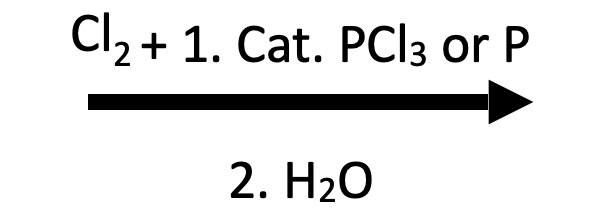

Butanoic acid → 2‑chlorobutanoic acid

1) Cl₂, PCl₃ 2) H₂O. The α‑CH₂ adjacent to CO₂H is selectively chlorinated; the highlight shows only the α‑Cl atom.

α‑Chloro acids can undergo SN2 reactions (e.g., NH₃ → α‑amino acids), so HVZ often appears in multistep syntheses.

2‑Methylpropanoic acid (no α‑H) → no reaction

t‑Butylacetic (pivalic) acid lacks an α‑hydrogen, so the acyl halide cannot enolize. HVZ fails—starting material is recovered.

Always check for α‑H before proposing HVZ; fully substituted α‑carbons (and benzylic acids) do not react.

Scope & Limitations

- Good substrates: Simple aliphatic acids (RCH₂CO₂H, R₂CHCO₂H) and phenylacetic-type acids that possess α‑H.

- Poor substrates: Benzoic acid, formic acid, t‑butylcarboxylic acid—anything lacking an α‑hydrogen.

- Halogen choice: Br₂/PBr₃ is the standard textbook case; Cl₂/PCl₃ works analogously but is seen less often in introductory courses. (I₂ is rarely used.)

- Over‑halogenation: The freshly formed α‑halo acid is less enolizable, so mono‑halogenation is the norm unless forcing conditions are applied.

- Functional group tolerance: Conditions are strongly acidic and produce HX; protect other acid-sensitive groups accordingly.

Practical Tips & Pitfalls

- Show the acyl halide: Do not draw X₂ halogenating the free acid; the acyl halide is the reactive species.

- Check α‑H before drawing products.

- Avoid radical arrows: HVZ proceeds through closed-shell enol chemistry, not through radicals like Hunsdiecker bromination.

- Workup choices: Water restores the acid; quenching with an alcohol instead gives α‑halo esters (useful synthetic variant).

- Downstream steps: α‑Bromo acids are excellent electrophiles for SN2 with NH₃, RNH₂, OH⁻, CN⁻, etc.—common on synthesis exams.

Exam-Style Summary

RCH₂CO₂H + X₂, PX₃ → RCH₂COX (acyl halide) → enol → electrophilic α‑halogenation → hydrolysis → RCHXCO₂H.

Requires an α‑H, uses closed-shell arrows, and typically stops at mono‑halogenation. “No α‑H” answers should explicitly state “no reaction.”

Interactive Toolbox

- Mechanism Solver — Play the 10-step HVZ animation (activation → halogenation → hydrolysis) and switch between the Br₂/PBr₃ or Cl₂/PCl₃ reagent set.

- Reaction Solver — Draw a carboxylic acid, check if it has an α‑H, and preview the α‑halo acid or a “no reaction” warning.

- IUPAC Namer — Paste the product SMILES to confirm names like “2‑bromopropanoic acid” or “2‑chlorobutanoic acid.”

FAQ / Exam Notes

Q1. Why is PBr₃ (or PCl₃) required for HVZ?

PX₃ converts the carboxylic acid into an acyl halide, which enolizes far more readily than the free acid; the enol of the acyl halide is the nucleophile that reacts with X₂ at the α‑carbon. (Source: Chemistry LibreTexts)

Q2. Does HVZ work with benzoic acid or t‑butanoic acid?

No. Both substrates lack an α‑hydrogen next to the carboxyl group, so the acyl halide cannot enolize and HVZ stops before halogenation. (Source: Chemistry LibreTexts)

Q3. Is HVZ a radical mechanism?

No. HVZ is a polar, closed-shell process that mirrors α‑halogenation of ketones/aldehydes via enols. Curved arrows should move lone pairs and π bonds, not fishhook arrows. (Source: masterorganicchemistry.com)

Q4. Can the reaction install more than one α‑halogen?

Not under introductory conditions. The first α‑halogen decreases further enolization, so mono‑halogenation dominates; forcing conditions are needed for multiple substitutions and are rarely tested. (Source: Alfa Chemistry)

Q5. How does HVZ relate to α‑amino acid synthesis?

An α‑bromo acid from HVZ can undergo SN2 with NH₃ to afford an α‑amino acid after workup—classically, propanoic acid → 2‑bromopropanoic acid → alanine. (Source: Wikipedia)