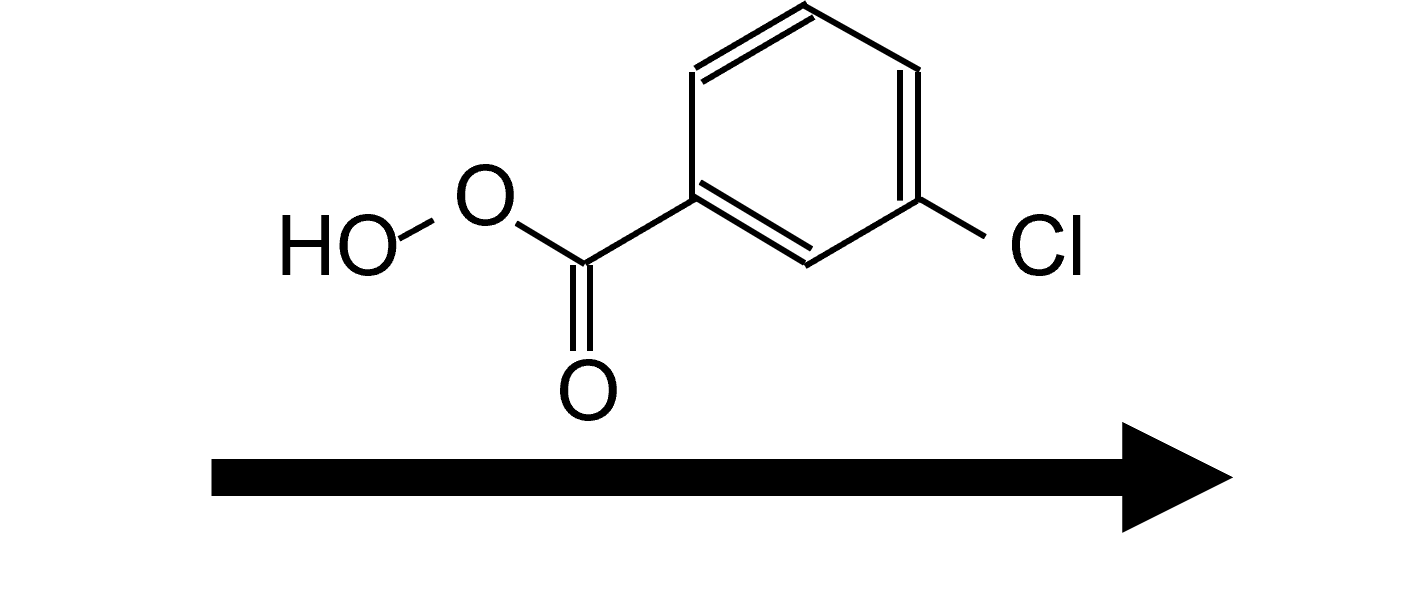

Baeyer–Villiger Oxidation (mCPBA, RCO₃H): Carbonyl → Ester/Lactone or Acid

Peracids such as meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (mCPBA) or a generic RCO₃H oxidize carbonyls through the Baeyer–Villiger reaction. Aldehydes migrate the hydride and become carboxylic acids; ketones insert oxygen next to the carbonyl to furnish esters (acyclic) or lactones (cyclic). The key sequence is peracid addition to form a Criegee intermediate, proton shuttling, and a concerted migration/O–O cleavage that releases the peracid-derived carboxylate. Migratory aptitude (tertiary ≳ aryl > secondary > primary > methyl) governs which side moves, and cyclic substrates expand by one atom. Because peracids are also strong epoxidation reagents, enones and isolated C=C bonds demand special attention.

Quick Summary

- Reagents/conditions: 1.1–2.0 equiv mCPBA or RCO₃H, CH₂Cl₂/CHCl₃ (0–25 °C), optional NaHCO₃ buffer to tame acidity.

- Outcome: Aldehyde → carboxylic acid (hydride migrates); ketone → ester or lactone (oxygen insertion adjacent to the carbonyl).

- Mechanism: Peracid addition forms the Criegee intermediate → proton organization → concerted migration with O–O cleavage → product + peracid-derived carboxylic acid.

- Migratory aptitude: tert-alkyl ≳ aryl > secondary > primary > methyl; hydride in aldehydes migrates fastest.

- Selectivity watch-outs: Peracids epoxidize C=C rapidly—enones and alkenes often require stronger Lewis-acid activation or stepwise planning.

- Stereochemical outcome: Migration proceeds with retention at the migrating center; no free carbocations are generated.

Mechanism (Baeyer–Villiger, 6 Steps)

Key checkpoints:

- Aldehydes are forced down the hydride-migration path; any competing migration would produce identical acids, so hydride wins by aptitude.

- Unsymmetrical ketones migrate the group that best stabilizes positive charge in the transition state (tertiary > secondary > primary, aryl competes strongly).

- Cyclic ketones expand by one atom to lactones; pay attention to ring strain—larger rings often migrate the less strained direction.

- Enones and isolated alkenes may epoxidize faster; check the Reaction Solver to forecast competing pathways.

Worked Examples

Cyclohexanone → Oxepan-2-one (ε-caprolactone)

mCPBA inserts oxygen and expands the six-membered ring to oxepan-2-one. Ring expansion by one atom is the hallmark lactone outcome for cyclic ketones.

3-Methyl-2-butanone → Methyl 2-methylpropanoate

The isopropyl side (higher aptitude) migrates first, giving methyl 2-methylpropanoate after oxygen insertion. Simple branched ketones respond cleanly under buffered peracid conditions.

Acetophenone → Phenyl ethanoate

Aryl groups migrate efficiently—mCPBA transforms acetophenone into phenyl ethanoate (phenyl acetate), illustrating resonance-stabilized migration.

2,2,4,4-Tetramethylpentan-3-one — No Baeyer–Villiger product

Heavily quaternary α-carbons provide no viable migrating group. RCO₃H only gives sluggish α-oxidation; Reaction Solver flags “no Baeyer–Villiger product” for this neopentyl-like ketone.

Scope & Limitations

- Substrate lane: Aldehydes always oxidize to carboxylic acids; ketones give esters (acyclic) or lactones (cyclic). α,β-Unsaturated ketones compete with epoxidation.

- Migratory aptitude: tert-alkyl ≳ aryl > secondary > primary > methyl; hydride migration dominates aldehydes. Bulky neopentyl systems stall.

- Functional groups: Free alkenes and enones epoxidize rapidly; strongly basic or nucleophilic sites (amines, thiols) may protonate or over-oxidize.

- Peracid choice: mCPBA is the workhorse; peracetic or trifluoroperacetic acid accelerates stubborn ketones but increases over-oxidation risk.

- Ring systems: Cyclic ketones expand by one atom; medium rings (<7) relieve strain, large rings can equilibrate to multiple lactones.

Practical Tips

- Buffer with NaHCO₃ to neutralize m-chlorobenzoic acid and protect base-sensitive groups.

- Add peracid slowly at 0–5 °C, then allow to warm; quench residual oxidant with Na₂SO₃ or Na₂S₂O₃ before aqueous workup.

- For enones that keep epoxidizing, add Lewis acids (BF₃·OEt₂) or protect the alkene prior to Baeyer–Villiger.

- Monitor migrations: reassign migrating groups if unexpected esters appear—aptitude and conformational alignment both matter.

Exam-Style Summary

Peracid oxidation proceeds via peracid addition to make the Criegee intermediate, proton migration, and a concerted shift that inserts oxygen and ejects carboxylate. Aldehydes migrate hydride to deliver carboxylic acids; ketones migrate the better group to form esters or lactones with retention at the migrating stereocenter. Watch for epoxidation of alkenes, ring expansion outcomes, and migratory aptitude ordering.

Common exam traps:

- Forgetting that hydride migration wins for aldehydes (no ester side products).

- Ignoring migratory aptitude—tertiary/aryl groups move before primary/methyl.

- Missing lactone ring expansion on cyclic ketones.

- Overlooking that epoxidation can outcompete Baeyer–Villiger on enones.

Related Reading

- Ketone enol halogenation (acid)

- Oxime formation & Beckmann rearrangement

- Aldehyde → carboxylic acid (chromate)

Interactive Toolbox

- Mechanism Solver — Use Mechanism Solver to see each step of the Baeyer–Villiger peracid mechanism along with descriptions of each step!

- Reaction Solver — Quickly find the product of any aldehyde or ketone reacted with mCPBA or a generic peracid!

- IUPAC Namer — Learn the naming ins and outs of the carbonyl starting materials and the ester/lactone or acid products they form.